Normally, the heartbeat begins in the right atrium when the sinoatrial (SA) node, a special group of cells, transmits an electrical signal across the heart. This signal spreads throughout the atria and to the atrioventricular (AV) node. The AV node connects to a group of fibers in

The sinoatrial node is the heart's pacemaker.

the ventricles that conducts the electrical signal and sends the impulse to all parts of the ventricles. This exact route must be followed to ensure that the heart pumps properly.

COMMON DYSRHYTHMIAS

Tachycardias

I. Sinus Tachycardia

a. Sinus node creates rate that is faster than normal (greater than 100)

b. Associated with physiological or psychological stress; medications, such as catecholamines, aminophylline, atropine, stimulants, and illicit drugs; enhanced automaticity; and autonomic dysfunction

II. Atrial Flutter

a. Occurs in the atrium and creates regular atrial rates between 250 and 400. Because AV node cannot keep up with conduction of all these impulses, not all atrial impulses are conducted into the ventricle, causing a therapeutic block at

the AV node.

III. Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

a. Rapid, irregular twitching of the atrial musculature with an atrial rate of 300 to 600 and a ventricular rate of 120 to

200 if untreated

b. Associated with advanced age, valvular heart disease, hyperthyroidism, pulmonary disorder, pulmonary disease,

alcohol ingestion (“holiday heart syndrome”), hypertension, diabetes, CAD, or after open-heart surgery

IV. Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia (PSVT, also called SVT)

a. Pathways in the AV node or atrium allow an altered conduction of electricity, causing a regular and fast rate of

sometimes more than 150 to 200.

b. Ventricle, sensing the electrical activity coming through the AV node, beats along with each stimulation.

c. Rarely a life-threatening event, but most people feel uncomfortable when PSVT occurs.

V. Ventricular Tachycardia (VT)

a. Rapid heartbeat initiated within the ventricles, characterized by three or more consecutive premature ventricular

beats with elevated and regular heart rate (such as 160 to 240 beats per minute)

b. Heart rate sustained at a high rate causes symptoms such as weakness, fatigue, dizziness, fainting, or palpitations

c. Potentially lethal disruption of normal heartbeat that can degenerate to ventricular fibrillation

VI. Ventricular Fibrillation (VF)

a. Aside from myocardial ischemia, other causes of ventricular fibrillation may include severe weakness of the heart

muscle, electrolyte disturbances, drug overdose, and poisoning.

b. Electrical signal is sent from the ventricles at a very fast and erratic rate, impairing the ability of ventricles to fill

with blood and pump it out, markedly decreasing cardiac output, and resulting in very low blood pressure and loss

of consciousness.

c. Sudden death will occur if VF not corrected.

Bradycardias

I. Sinus Bradycardia

a. Rarely symptomatic until heart rate drops below 50, then fainting or syncope may be reported

b. Causes include hypothyroidism, athletic training, sleep, vagal stimulation, increased intracranial pressure, MI, hypovolemia, hypoxia, acidosis, hypokalemia and hyperkalemia, hyperglycemia, hypothermia, toxins, tamponade, tension pneumothorax, thrombosis (cardiac or pulmonary), and trauma.

c. Medications, such as beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and amiodarone, also slow the heart rate (AHA, 2005).

II. Sick Sinus Syndrome (SSS)

a. Varity of conditions affecting SA node function, including bradycardia, sinus arrest, sinoatrial block, episodes of

tachycardia, and carotid hypersensitivity

b. Signs and symptoms related to cerebral hypoperfusionc. May be associated with rapid rate (tachycardia) or alternate between too fast and too slow (bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome). A long pause (asystole) may occur between heartbeats, especially after an episode of tachycardia.

III. Heart Blocks

a. First-degree AV block

i. Asymptomatic; usually an incidental finding on electrocardiogram (ECG)

b. Second-degree AV (type I and type II)

i. Usually asymptomatic, although some clients can feel irregularities (palpitations) of the heartbeat, or syncope

may occur, which usually is observed in more advanced conduction disturbances such as Mobitz II AV block

ii. Medications affecting AV node function, such as digoxin, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, may contribute

c. Third-degree AV block (also called complete heart block)

i. May be associated with acute MI either causing the block or related to reduced cardiac output from bradycardia in

the setting of advanced atherosclerotic CAD ii. Symptomatic with fatigue, dizziness, and syncope and possible loss of consciousness

iii. Can be life-threatening, especially if associated with heart failure

Other Dysrhythmias

I. Premature Atrial Complex (PAC)

a. Electrical impulse starts in the atrium before the next normal impulse of the sinus node.

b. Causes include caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine use, stretched atrial myocardium; anxiety; hypokalemia; and hypermetabolic states (pregnancy), or may be related to atrial ischemia, injury, or infarction.

II. Premature Ventricular Contraction (PVC)

a. Electrical signal originates in the ventricles, causing them to contract before receiving the electrical signal from the atria.

b. PVCs not uncommon and are often asymptomatic.

c. Increase to several per minute may cause symptoms such as weakness, fatigue, dizziness, fainting, or palpitations.

d. Irritability of the heart demonstrated by frequent and or multiple back-to-back PVCs can lead to VF.

Care Settings

Generally, minor dysrhythmias are monitored and treated in the community setting; however, potential life-threatening situations (including heart rates above 150 beats per minute) may require a short inpatient stay.

Nursing Priorities

1. Prevent or treat life-threatening dysrhythmias.

2. Support client and significant other (SO) in dealing with anxiety and fear of potentially life-threatening situation.

3. Assist in identification of cause or precipitating factors.

4. Review information regarding condition, prognosis, and treatment regimen.

Discharge Goals

1. Free of life-threatening dysrhythmias and complications of impaired cardiac output and tissue perfusion.

2. Anxiety reduced and managed.

3. Disease process, therapy needs, and prevention of complications understood.

4. Plan in place to meet needs after discharge.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS: risk for decreased Cardiac Output

Risk factors may include

Altered electrical conduction

Reduced myocardial contractility

Possibly evidenced by

(Not applicable; presence of signs and symptoms establishes an actual diagnosis)

Desired Outcomes/Evaluation Criteria—Client Will

Cardiac Pump Effectiveness

Maintain or achieve adequate cardiac output as evidenced by BP and pulse within normal range, adequate urinary output, palpable pulses of equal quality, and usual level of mentation.

Display reduced frequency or absence of dysrhythmia(s).

Participate in activities that reduce myocardial workload.

ACTIONS/INTERVENTIONS

Dysrhythmia Management

Independent

Palpate radial, carotid, femoral, and dorsalis pedis pulses, noting rate, regularity, amplitude (full or thready), and symmetry.

Document presence of pulsus alternans, bigeminal pulse, or pulse deficit.

Auscultate heart sounds, noting rate, rhythm, presence of extra heartbeats, and dropped beats.

Monitor vital signs. Assess adequacy of cardiac output and tissue perfusion, noting significant variations in BP, pulse

rate equality, respirations, changes in skin color and temperature, level of consciousness and sensorium, and urine

output during episodes of dysrhythmias.

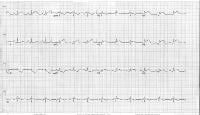

Determine type of dysrhythmia and document with rhythm strip if cardiac or telemetry monitoring is available:

Sinus tachycardia

Sinus bradycardia

Atrial dysrhythmias, such as PACs, atrial flutter, AF, and atrial supraventricular tachycardias (i.e., paroxysmal atrial

tachycardia [PAT], multifocal atrial tachycardia [MAT], SVT)

Ventricular dysrhythmias, such as PVCs and ventricular premature beats (VPBs), VT, and ventricular flutter and VF

Heart blocks

Provide calm and quiet environment. Review reasons for limitation of activities during acute phase.

Demonstrate and encourage use of stress management behaviors such as relaxation techniques; guided imagery;

and slow, deep breathing.

Investigate reports of chest pain, documenting location, duration, intensity (0 to 10 scale), and relieving or aggravating factors. Note nonverbal pain cues, such as facial grimacing, crying, changes in BP and heart rate.

Be prepared to initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), as indicated.

Collaborative

Monitor laboratory studies, such as the following:

Electrolytes

Medication and drug levels

Administer supplemental oxygen, as indicated.

Prepare for and assist with diagnostic and treatment procedures such as EP studies, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and cryoablation (CA).

Administer medications, as indicated, for example:

Potassium

Antidysrhythmics, such as the following:

Class I drugs:

Class Ia, such as disopyramide (Norpace), procainamide

(Procan SR), quinidine (Cardioquin), and moricizine

(Ethmozine)

Class Ib, such as lidocaine (Xylocaine), phenytoin (Dilantin), tocainide (Tonocard), and mexiletine (Mexitil)

Class Ic, such as flecainide (Tambocor) and propafenone (Rhythmol)

Class II drugs, such as atenolol (Tenormin), propranolol (Inderal), nadolol (Corgard), acebutolol (Sectral), esmolol (Brevibloc), sotalol (Betapace), and bisoprolol (Zebeta)

Class III drugs, such as bretylium tosylate (Bretylol), amiodarone (Cordarone), sotalol (Betapace), ibutilide (Corvert), and dofetilide (Tikosyn)

Class IV drugs, such as verapamil (Calan), nifedipine (Procardia), and diltiazem (Cardizem)

Class V drugs, such as atropine sulfate, isoproterenol (Isuprel), and cardiac glycosides (digoxin [Lanoxin])

Adenosine (Adenocard)

Prepare for and assist with elective cardioversion.

Assist with insertion and maintain pacemaker (external or temporary, internal or permanent) function.

Insert and maintain intravenous (IV) access.

Prepare for surgery, such as aneurysmectomy, CABG, and Maze, as indicated.

Prepare for placement of ICD when indicated.

RATIONALE

Differences in equality, rate, and regularity of pulses are indicative of the effect of altered cardiac output on systemic

and peripheral circulation.

Specific dysrhythmias are more clearly detected audibly than by palpation. Hearing extra heartbeats or dropped beats

helps identify dysrhythmias in the unmonitored client.

Although not all dysrhythmias are life-threatening, immediate treatment may be required to terminate dysrhythmia in the presence of alterations in cardiac output and tissue perfusion.

Useful in determining need and type of intervention required.

Tachycardia can occur in response to stress, pain, fever, infection, coronary artery blockage, valvular dysfunction,

hypovolemia, hypoxia, or as a result of decreased vagal tone or of increased sympathetic nervous system activity

associated with the release of catecholamines. Although it generally does not require treatment, persistent tachycardia may worsen underlying pathology in clients with ischemic heart disease because of shortened diastolic filling time and increased oxygen demands. These clients may require medications.

Bradycardia is common in clients with acute MI (especially anterior and inferior) and is the result of excessive parasympathetic activity, blocks in conduction to the SA or AV nodes, or loss of automaticity of the heart muscle.

Clients with severe heart disease may not be able to compensate for a slow rate by increasing stroke volume; therefore, decreased cardiac output, HF, and potentially lethal ventricular dysrhythmias may occur.

PACs can occur as a response to ischemia and are normally harmless, but can precede or precipitate AF. Acute and chronic atrial flutter or fibrillation (the most common dysrhythmia) can occur with coronary artery or valvular disease and may or may not be pathological. Rapid atrial flutter or fibrillation reduces cardiac output as a result of

incomplete ventricular filling (shortened cardiac cycle) and increased oxygen demand.

PVCs or VPBs reflect cardiac irritability and are commonly associated with MI, digoxin toxicity, coronary vasospasm,

and misplaced temporary pacemaker leads. Frequent, multiple, or multifocal PVCs result in diminished cardiac output

and may lead to potentially lethal dysrhythmias, such as VT or sudden death or cardiac arrest from ventricular flutter or VF. Note: Intractable ventricular dysrhythmias unresponsive to medication may reflect ventricular aneurysm.

Polymorphic VT (torsades de pointes) is recognized by inconsistent shape of QRS complexes and is often related to use of drugs such as procainamide (Pronestyl), quinidine (Quinaglute), disopyramide (Norpace), and sotalol (Betapace).

Reflect altered transmission of impulses through normal conduction channels (slowed, altered) and may be the result of MI, CAD with reduced blood supply to SA or AV nodes, drug toxicity, and sometimes cardiac surgery. Progressing heart block is associated with slowed ventricular rates, decreased cardiac output, and potentially lethal ventricular dysrhythmias or cardiac standstill.

Reduces stimulation and release of stress-related catecholamines, which can cause or aggravate dysrhythmias and vasoconstriction, increasing myocardial workload.

Promotes client participation in exerting some sense of control in a stressful situation.

Reasons for chest pain are variable and depend on underlying cause. However, chest pain may indicate ischemia due

to altered electrical conduction, decreased myocardial perfusion, or increased oxygen need, such as impending or evolving MI.

Development of life-threatening dysrhythmias requires prompt intervention to prevent ischemic damage or death.

Imbalance of electrolytes, such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium, adversely affects cardiac rhythm and contractility.

Reveal therapeutic and toxic level of prescription medications or street drugs that may affect or contribute to presence of dysrhythmias.

Increases amount of oxygen available for myocardial uptake, reducing irritability caused by hypoxia.

Treatment for several tachycardia dysrhythmias, including SVT, atrial flutter, Wolf-Parkinson-White ( WPW) syndrome, AF, and VT, is often carried out as first-line treatment via heart catheterization or angiographic procedures. After rhythm is confirmed with EP study, the client will then often have either an RFA or CA to terminate or disrupt the dysfunctional pattern. Medications may be tried first or added after ablation for increased treatment success.

Correction of hypokalemia may be sufficient to terminate some ventricular dysrhythmias. Note: Potassium imbalance is the number one cause of AF.

Class I drugs depress depolarization and alter repolarization, stabilizing the cell. These drugs are divided into groups a,

b, and c, based on their unique effects.

These drugs increase action potential, duration, and effective refractory period and decrease membrane responsiveness, prolonging both QRS complex and QT interval. This also results in decreasing myocardial conduction velocity and excitability in the atria, ventricles, and accessory pathways.

They suppress ectopic focal activity. Useful for treatment of atrial and ventricular premature beats and repetitive dysrhythmias, such as atrial tachycardias and atrial flutter and AF. Note: Myocardial depressant effects may be potentiated when class Ia drugs are used in conjunction with any drugs possessing similar properties.

These drugs shorten the duration of the refractory period (QT interval), and their action depends on the tissue affected and the level of extracellular potassium. These drugs have little effect on myocardial contractility, AV and intraventricular conduction, and cardiac output. They also suppress automaticity in the His-Purkinje system. Drugs of choice for ventricular dysrhythmias, they are also effective for automatic and re-entrant dysrhythmias and digoxininduced dysrhythmias. Note: These drugs may aggravate myocardial depression.

These drugs slow conduction by depressing SA node automaticity and decreasing conduction velocity through the atria, ventricles, and Purkinje’s fibers. The result is prolongation of the PR interval and lengthening of the QRS complex. They suppress and prevent all types of ventricular dysrhythmias. Note: Flecainide increases risk of druginduced dysrhythmias post-MI. Propafenone can worsen or cause new dysrhythmias, a tendency called the “pro-arrhythmic effect.”

Beta-adrenergic blockers have antiadrenergic properties and decrease automaticity. They reduce the rate and force of cardiac contractions, which in turn decrease cardiac output, blood pressure, and peripheral vascular resistance.

Therefore, they are useful in the treatment of dysrhythmias caused by SA and AV node dysfunction, including SVTs, atrial flutter and AF. Note: These drugs may exacerbate bradycardia and cause myocardial depression, especially when combined with drugs that have similar properties.

These drugs prolong the refractory period and action potential duration, consequently prolonging the QT interval. They decrease peripheral resistance and increase coronary blood flow. They have anti-anginal and anti-adrenergic properties.

They are used to terminate VF and other life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias and sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias, especially when lidocaine and procainamide are not effective. Note: Sotalol is a nonselective beta

blocker with characteristics of both class II and class III.

Calcium antagonists, or calcium channel blockers, slow conduction time through the AV node, prolonging PR interval to decrease ventricular response in SVTs, atrial flutter and AF. Calan and Cardizem may be used for bedside conversion of acute AF.

Miscellaneous drugs useful in treating bradycardia by increasing SA and AV conduction and enhancing automaticity.

Cardiac glycosides may be used alone or in combination with other antidysrhythmic drugs to reduce ventricular rate in presence of uncontrolled or poorly tolerated atrial tachycardias or atrial flutter and AF.

First-line treatment for PSVT. Slows conduction and interrupts reentry pathways in AV node. Note: Contraindicated in

clients with second- or third-degree heart block or those with SSS who do not have a functioning pacemaker.

May be used in AF after trials of first-line drugs, such as atenolol, metoprolol, diltiazem, and verapamil, have failed to control heart rate or in certain unstable dysrhythmias to restore normal heart rate or relieve symptoms of heart failure.

Temporary pacing may be necessary to accelerate impulse formation in bradydysrhythmias, synchronize electrical impulsivity, or override tachydysrhythmias and ectopic activity to maintain cardiovascular function until spontaneous pacing is restored or permanent pacing is initiated.

These devices may include atrial and ventricular pacemakers and may provide single chamber or dual chamber pacing. The placement of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) is on the rise.

Patent access line may be required for administration of emergency drugs.

Differential diagnosis of underlying cause may be required to formulate appropriate treatment plan. Resection of ventricular aneurysm may be required to correct intractable ventricular dysrhythmias unresponsive to medical therapy.

Surgery such as CABG may be indicated to enhance circulation to myocardium and conduction system. Note: A Maze procedure is an open heart surgical procedure sometimes used to treat refractive AF by surgically redirecting electrical conduction pathways.

This device may be surgically implanted in those clients with recurrent, life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias unresponsive to tailored drug therapy. The latest generation of devices can provide multilevel or “tiered” therapy, that is, antitachycardia and antibradycardia pacing, cardioversion, or defibrillation depending on how each device is programmed.